psalms and the witness of Fr. Daniel Berrigan

During our pastors’ week in Colorado, after wandering around in the mountains, we focused our afternoon conversations on William Stringfellow and Wendell Berry. Each day we also included reflections from Uncommon Prayer: A Book of Psalms, by Fr. Daniel Berrigan. The psalms have always been a prayer book for Christians and Jews. In his commentary, Berrigan describes carrying around a pocket edition of the psalms, in French. “In a dry time on earth, it is a joy to return again and again to the psalms. Their waters hiss on the tongue, as though laid against hot metal, or seared flesh. A dry time indeed.”

Ordained into the company of Presbyterians, originally known as “the psalm singers,” I was early introduced to them in daily prayers, and every Sunday in worship we sang a psalm. Our current congregation does not sing psalms weekly, and I miss that practice very much. I’m learned from John Calvin who referred to them as “the anatomy of the soul,” because they expressed the joy, sorrow, wonder, anguish, anger and bewilderment of being a human. I appreciated listening again to Berrigan’s “take” on them.

He writes, “Years and years ago, when I was first introduced to the psalms, my love for them took root in a more or less common assumption: that the world made sense, that lightheartedness and joy were our patrimony, that over and above mere survival, life was concert, a very conspiracy of hope. […] They have stolen our joy! That is how a biblical indictment of modern life might go. I’m trying to say (and the saying is difficult indeed) that the vision of humankind, the simple, truthful sense of who we are offered by the psalms, is in principal denied by the spirit and drift of the world. We are here and now; and here and now the glory of God is under lethal assault. So is our glory, which is to praise, to invoke, to believe, to live and rejoice in the beloved community. Noting that glory, that dignity I grew to love the psalms. To pray the psalms with even half a heart was to be comforted and discomfited, set in motion, set in stillness, set free, set on edge, led outside, led within.”

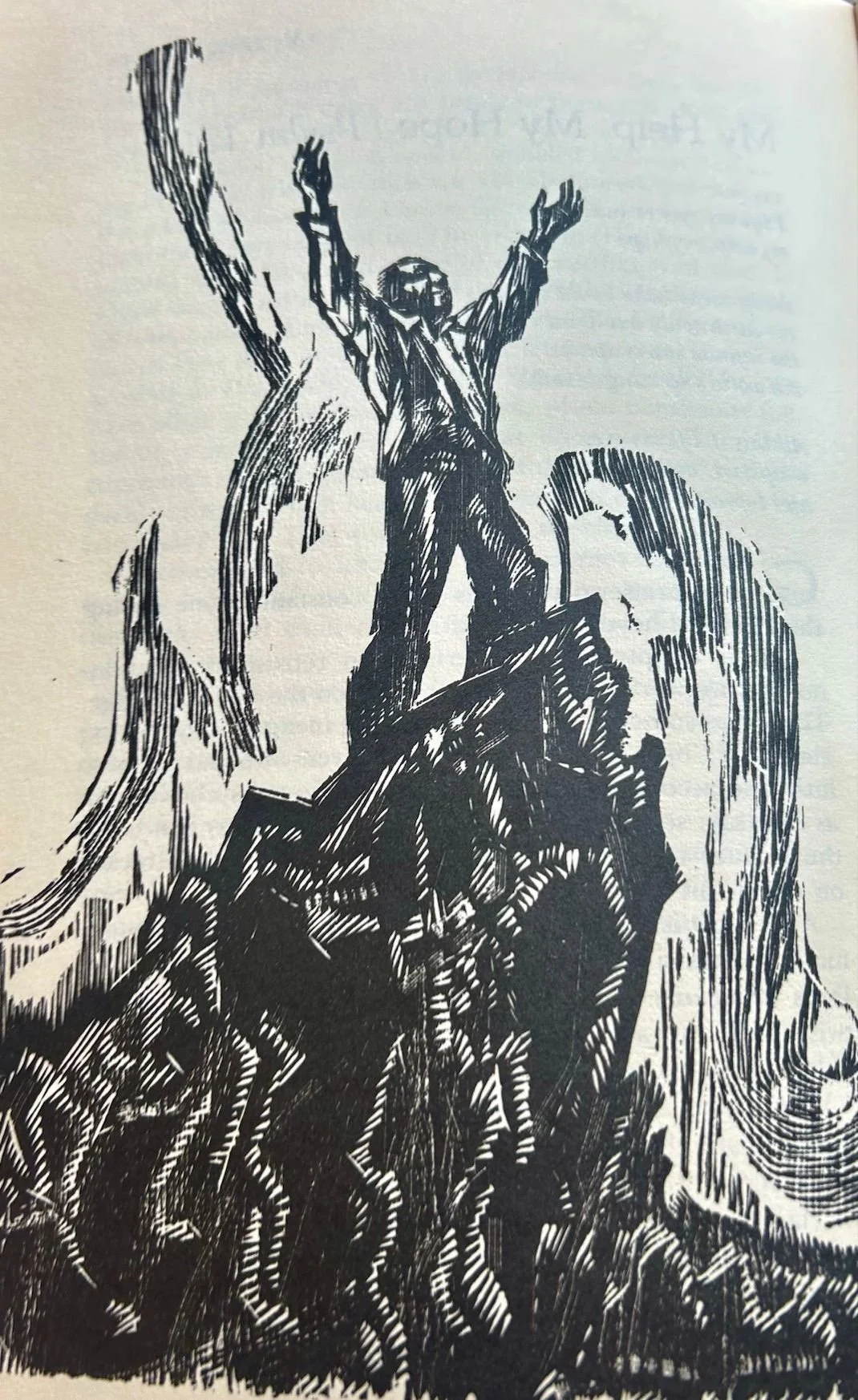

The woodcut by Robert McGovern on Psalm 121, is among several in the book.

That Berrigan could find encouragement, light, manna-for-the-soul, even while standing forthright facing horrors of humanity, is an inspiration for my own practices in this wrecked world. He writes, “I remember saying them in the rubble and bomb shelters of Hanoi, in the Baltimore courtroom, in Danbury prison. There we sat finally (it seemed fairly final at the time), a group of us, stuck fast for the duration. But not so stuck, as it turned out, that we couldn’t be set free. The psalms were my freedom songs.”

How then to navigate our way in the troubled world? What is the compass that guides our prayer and practice?

“Long before I went to jail, my family and friends had accepted the idea that the scripture, more specifically the psalms, were our landmark, a source of sanity in an insane time. The psalms spoke up for my soul, for survival: they pled for all, they bonded us when when the world would break us like dry bones. They made sense, where the ‘facts’ - scientific, political, religious - made only nonsense. For me, the psalms gave coloration and texture to life itself; gave weight to silence, the space between words that, like the white in a Cezanne painting, intensify form and color.”

Uncommon Prayer includes Berrigan’s poetic translations. Here is Psalm 121:

I lift my eyes to you

my help, my hope

the heavens (who could imagine?)

the earth (only our Lord)

the infinite starry spaces

the world’s teeming breadth.

All this. I lift my eyes

—upstart, delighted—

and I praise.